I’ve been interested in dog training since I was 12 years old and my family welcomed a Cocker Spaniel X puppy we named Cherry. I was not, however, one of these children that teaches their dogs amazing tricks. I tried but nothing ever came of it. My mum took Cherry to obedience school and I often tagged along. He learned to listen to us well enough. I grew up in an apartment in Vienna, Austria, and back then dogs were only de-sexed for health reasons which meant that the majority of dogs remained entire for their whole life. Apartment life requires taking the dog out three to four times a day for toileting. Once a day we went for an hour walk including off-lead time. All of this we managed without an incident ever even though between the age of three and six years Cherry was quite reactive on-lead towards other males.

My first real dog training challenge arrived in the form of a Border Collie, Fraser, who we adopted from another family when he was 6 years old. I was in my mid 20ies. Already living with us were a German Shepherd and a German Shepherd X, both re-homed as well. Fraser just did what he wanted, always found ways to escape the yard and go for a wander, he didn’t seem to care about anyone much, always preoccupied in his own mind he took no notice of us. At night he didn’t sleep but endlessly paced the house. Our vet who had a Border Collie too mentioned Jon Katz’s book “A dog year: Rescuing Devon, the most troublesome dog in the world”. It was an eye opening and entertaining read.

I moved to Australia just before I turned 40. Soon after, I adopted Louie, a Kelpie X, approximately 8 years old. After some escaping (purely opportunistic) and chewing up a library book as well as my favourite beanie knitted by my best friend (in protest of being left home alone), I knew I needed help. After some research I decided on an obedience school an hour’s drive away. What had sold me to offset the inconvenience of travelling the distance was that all the trainers’ dogs stayed on their mats in spite of the bustle around them, and the head trainer’s dog, a lab called Ella, who responded immediately to everything she was asked during the free introduction class and hung around, off-lead, neither wandering off nor engaging with anyone. A lab!!! All the labs I knew were crazy. I wanted a dog like that. Louie and I signed up and breezed through the levels, passing into the advanced class within five months. That’s when I decided to take their course to become a dog trainer.

The common understanding of animal training is that it happens through conditioning. There are two kinds – Classic Conditioning and Operant Conditioning.

Classic Conditioning

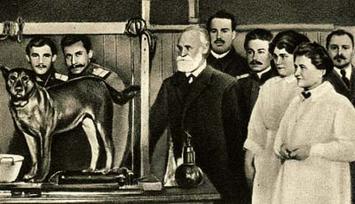

Russian researcher Ivan Pavlov’s experiments with dogs which led to describing Classic Conditioning are world famous. He rang a bell, followed by presenting food to the dogs he studied. Soon, the dogs started salivating when they heard the sound of the bell before the food arrived. A previously meaningless sound became a powerful stimulus, eliciting an involuntary physiological response (salivating) as well as emotional response (happy anticipation). We all have experiences of classic conditioning. Certain sounds, sights, thoughts trigger unconscious responses such as the sound of a dentist’s drill or looking at a piece of chocolate cake. We have no control over these responses. Other examples are your dog’s reaction when they see you picking up their lead or your car keys or, when out on a walk you approach that fence behind which sometimes a dog barks.

approximately 1925

image via commons.wikimedia.org

Operant Conditioning

American psychologist Dr. B.F. Skinner studied what is now known as Operant Conditioning. The basic idea is that there is an association created between a behaviour and its consequence. It works with reinforcement and/or punishment. We are likely to repeat behaviour that is rewarding and suppress behaviour that produces unpleasant consequences. What is perceived as reinforcing is relative, not absolute. For example, water is a positive reinforcer for ducks but a negative one for most cats. What might be adequately reinforcing in one environment is utterly uninteresting in another one that provides something more desirable. For example, treats might work well at home but not when out on a walk.

on the most effective method of teaching/learning in the 1950ies.

Image provided courtesy of www.all-about-psychology.com/

What about dog training?

Basically, there are two approaches to dog training. The traditional do as I say or else on the one hand and positive reinforcement on the other. Both are based on Operant Conditioning.

The first school of thought has commands for their dogs and punishment of some kind if the dog doesn’t comply. The classic smack on the nose with the rolled up newspaper, a jerk on the lead or any other action functioning as an aversive that the dog learns to try and avoid. Truthfully, it’s training through intimidation. It works well in many cases yet it comes at a cost.

The second school of thought, positive reinforcement, is based on Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), the science of learning and behaviour. Often it’s called food-based reward training or clicker training. It’s a non confrontational way of teaching a dog. Behaviours are taught and put on cue once well understood. If training goals are not achieved the dog doesn’t get blamed but instead the training plan gets revised. There are no punishments because research has shown that using aversives (punishment) only stops ongoing behaviour but doesn’t produce a predictable outcome in the future, whereas a reinforcer does strengthen behaviour in the future. Also, punishment often only is effective in the presence of the punisher, in their absence, the dog might still pursue the unwanted behaviour.

And what about the effects on the ‘trainer’ who uses aversives? If we hurt or scare a dog regularly – and this includes inflicting psychological threats and pain – it becomes a reinforcing habit. Every time we succeed, we have proof that what we do works. But then there are the times when our method doesn’t work and we feel justified in escalating our measures.

From my own experience of working with such methods, especially when new to it, it can create a mindset of taking a dog’s behaviour really personally as well as judging a dog’s actions or failure to comply as “being stubborn” or “being a little shit” or “giving you the finger.” Working with aversives, I got quite worked up myself. I was impatient with and unkind to my dog. I felt frustrated often. Neither of us really enjoyed it, what with all the tension in the air. I am not unique that way, this is a common phenomenon when using coercion as a training method.

Positive reinforcement – the art of giving presents

Many people try positive reinforcement training and find it doesn’t work! Probably the biggest reason why people’s attempts fail is poor timing. Laggard reinforcement is unclear communication. On the other hand, reinforcement given too early is bribery which works sometimes but not when there is something more interesting around. Such set-up and timing is not conducive to success. So people dismiss this method, believing it doesn’t work.

Another reason why people might not succeed is that their dog isn’t food motivated. They don’t understand that reinforcements come in many ways, food only being one of them. In order to be reinforcing, the item or action chosen as a reinforcer must be something the learner (your dog!) wants and appreciates. What might work in one environment might not work at all in a different one. You need to be observant and note what your dog finds reinforcing under what circumstances.

Some people say it’s impractical to always have food on you but constant reinforcement is only needed in the learning stages of training. In order to maintain an already learned behaviour it’s actually important to use reinforcement only occasionally, and on a random basis.

Did you know that positive reinforcement training is used in modern zoos and animal sanctuaries to not only provide meaningful activities for the captivated animals but also to help with regular procedures necessary for managing the animals’ health? Examples are teaching a giraffe to walk through a chute and step onto the scales to be weighed, and teaching hyenas to hold still and voluntarily offer their throats for drawing blood when needed.

If there are no consequences, nobody would follow the rules!

Most of us are very accustomed to the first training style, the one using coercion because it is widely used in our society. Punishment seems normal and therefore acceptable even though nowadays we prefer calling it “giving a consequence”.

“What’s the big deal anyways? If there are no consequences, nobody would follow the rules! And we all turned out alright!” you might think. Studies, however, show how damaging this kind of learning environment is – to the learner-teacher relationship as well as to the mental health of everyone involved. There are many documented ill effects of using aversives. Here is a short summary and here are scientific references on the topic.

With so much at stake, why is this training style still so pervasive? Because of Darwin misconstrued and wolves misunderstood. Let me explain.

Survival of the fittest

I don’t know how it happened. If it was by mistake or by design. Charles Darwin’s insights in his most famous book “Of the Origin of Species” have been misrepresented. Did you know that in the over 500 pages he only uses “survival of the fittest” twice but over a hundred times he mentions care and love as the highest form of cooperation, the most successful survival strategy? The term survival of the fittest has been grossly misconstrued to mean that aggression, competition and dominance are biological or even evolutionary imperatives. A celebration of selfishness. Might is right. Bigger is better. Wrong, say the findings of neurobiologists like Dr. Gerald Hüther, Dr. Joachim Bauer and others who confirm with modern scientific methods what Darwin meant by survival of the fittest, meaning care, love, connection and cooperation are the qualities needed for success and to thrive.

Check out David Loye’s The Darwin Project, dedicated to telling how we can change the world for the better by changing the story we live by.

I love this image because it excudes such warmth compared to the usual black and white photos of him with a stern facial expression.

From a public domain image on Wikimedia Commons, originally from Vanity Fair, 1871.

The dominance myth

In the survival of the fittest mindset, observations of the behaviours in captivated wolf packs just confirmed what was already accepted as true. Dominance in Dogs. Fact or Fiction? by Barry Eaton gives a well-researched update on long-held believes about wolves and dogs. It’s important to understand why a dog is not a wolf, though clearly they are related. There are many behaviours they share. The wolf is the ancestor of the dog but a combination of evolutionary processes and selective breeding by humans has made the wolf and dog very different animals. But, and this is the important bit, what we thought we knew about wolf behaviour actually turns out to be inaccurate because the research this knowledge is based on was done on wolves in captivity. Why does that matter? David L. Mech, a renown expert on wolf behaviour, says, “The typical wolf pack should be viewed as a family with the adult parents guiding the activities of the group and sharing group leadership in a division of labour. […] If the kill were small, the breeders would eat first, but if food were scarce, the pups would be fed first. If the kill were big enough, all pack members, regardless of rank, feed together.”

Barry Eaton further explains, “So, the idea that the alpha wolves always eat first is largely untrue and indeed pups are fed first to ensure their survival. Much of what we thought we knew about wolf behaviour came from the study of captive wolves. Contrary to the family values of a naturally free pack, wolves in a captive pack do make frequent challenges to gain higher status. The higher the position at stake the more vigorously a campaign is conducted. A captive pack will have unacquainted wolves of different ages and gender brought together from different sources. In this situation, a certain amount of social tension is likely to exist, particularly during the mating season. Under these circumstances there is often a dominant male and female, and there are frequent fights among younger wolves for higher status. Within the captive pack, managed and manipulated by man, wolves will be unable to express many of their natural behaviours and will be unable to leave the pack to find a mate as free wolves do.”

What about feral dogs? “Coppinger and Coppinger’s research (2001) has shown that even feral dogs do not need to form packs in order to survive. If all the vital elements of survival are available – food, water and shelter – they are happy to live independently or harmoniously in small groups. […] Feral dogs live a very different lifestyle to that of wolves. These dogs frequently join and leave the group and there are not the complex rules that wolves live by. The social structure is very loose, whereas a wolf pack is very cohesive. Few, if any, feral dogs are related, unlike the family unit of a wolf pack.” (quote from Dominance in Dogs. Fact or Fiction?)

Let’s read about domestic dogs from the book. “We have now established that dogs are not wolves and that the wolf packs formed in the wild are basically cooperative family units with the breeding pair looking after and guiding their young. Yet many people seem to really want to believe that dogs are pack animals and if not kept under strict control will seek dominance over the other members of what we think are a pack. Part of this thinking is probably how we view the world from our own human perspective. Humans live in a culture of hierarchies. From cradle to grave, whatever walk of life, we are almost always answerable to someone. It might seem natural then to pass this hierarchical mindset onto our relationship with our dogs and believe that dogs would perceive themselves as being part of our ‘pack.’ Therefore, they must have their place within it and to meet with our own perceptions of the appropriate hierarchical structure, their place should be at the bottom.”

If this is all new to you, I understand it’s a lot to take in. Perhaps, you are just feeling immensely relieved right now or incredibly uncomfortable. Allow these seeds to fall on the ground of your mind and see what – if anything – germinates and grows from them.

Whether you choose to train your dog through the contrast of right and wrong (traditional methods) or via cooperative ways (positive reinforcement), one big problem both methods share is how to get and keep your dog’s attention to actually be able to teach them something. Over-excitement and distraction can be so frustrating and training becomes a struggle. Of course, each method offers answers to this problem. The traditional method uses psychological and physical intimidation (and rewards acquiescence), positive reinforcement is all about creating an undisturbed learning environment and keeping training sessions super short and fun. Both of these approaches work for some but it seems the majority of people fail to make it work. Many hang in there and over time get the hang of it but it’s such a drag.

The approach of all dog training methods to behaviour modification is to influence and control the behaviour. So, for example, teaching a dog not to jump up is done by either punishing all unwanted behaviours (and praising the wanted ones) or reinforcing the dog’s wanted behaviours and ignoring the others (though ideally, the set-up would be such that the dog couldn’t make a wrong choice at all). Makes perfect sense? Well, in the conventional understanding it does. But what if the situation would be approached differently altogether? What if a dog could be taught to feel calm in previously exciting situations and as a by-product their behaviour changes? If we feel excited different behaviours are cued than if we feel relaxed and calm. And that is how The Trust Technique approaches behaviour modification. A dog that feels chill when visitors arrive will not jump up. A dog that feels confident and no longer on edge when seeing another dog will not lunge, growl or bark. A dog that feels unconcerned and safe will not panic anymore when left home alone.

What if you are not after behaviour modification but just want to teach your dog a trick or skill? The process is more enjoyable and retention rates much higher if first you can create a state of calm alertness for both, yourself and your dog, with The Trust Technique. That way, the two of you are relaxed, focussed and engaged. Doing things together that way promotes ease, joy, connection, interest, openness and trust. You’ll both look forward to your next learning session together. When there is no more fear in any of its many disguises, trusted cooperation unfolds in an atmosphere of gratitude and mutual adoration.

Advancing my skills by becoming a Trust Technique practitioner has widened the scope of my ability to help people and their dogs – and other animals. But first, I learned the method for myself and my own animals, experiencing a deepening of my understanding of the human-animal relationship. Applying the Trust Technique with my own and especially my foster dogs, was a fascinating journey. I was becoming much more effective in helping shut-down, nervous, scared or over-excited dogs. The pièce de résistance for me was working with Henry, a 2-year old Neapolitan Mastiff with huge separation anxiety.

Henry was my foster dog. His separation anxiety was to such a degree that his behaviours were extreme. He once even jumped through a glass window (before he was in my care). His vocalisations sounded concerning (wailing, howling and barking) and could go on for hours without lessening. In terms of escaping, Houdini could have learned a trick or two from Henry, squeezing through spaces a Jack Russel could hardly fit through, let alone a big Mastiff! Breaking out of the house or a crate or weaseling out of a harness was child’s play for him. Aside from the separation anxiety, Henry really was only interested in doing his own thing. Anything asked of him he didn’t feel like doing, he would either ignore or throw himself onto the ground, melting into a massive puddle at my feet that couldn’t be budged.

It didn’t matter if other dogs were left at home with him, panic struck when all humans were gone. It took six intense weeks of applying the Trust Technique to help him be calm and confident when left alone for short periods of times (up to an hour). In terms of working on his ability to cooperate with me when I asked something of him, such as to hop into the car or even simply to sit, any coercive approach landed me nowhere other than feeling utterly frustrated. Trying to wrangle a dog his size requires a lot of physical strength. I remember leaning my whole weight on his backend in a futile attempt to make him sit. It’s funny now, but it wasn’t then. I needed to hone my positive reinforcement skills. Even though Henry was quite food motivated, there is an art to the method that I didn’t possess yet. Luckily, I am a quick learner. My timing, choice of reinforcers and my set-up smarts improved rapidly. But the biggest contributing fact to Henry’s interest and willingness to cooperate were our Trust Technique sessions. The thus developed rapport and relationship provided the best possible learning environment for teaching him what’s necessary to be a happy dog living with humans. Though extensive rehoming efforts were made, eventually it became clear that Henry belonged with us. And what a happily ever after it has been ever since.

Leave a Reply